A.G. Noorani blames Patel for downfall of Hyderabad

DC | DECCAN CHRONICLEPublishedNov 30, 2013, 2:00 pm ISTUpdatedMar 18, 2019, 9:07 pm IST Noted columnist and writer Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed Noorani said the Army should not be used against a civilian population as a way of resolving problems. He was addressing a gathering here at Jubilee Hall on Friday after the launch of his book The Destruction of Hyderabad. Referring to the history of the Police Action in Hyderabad and Operation Blue Star in Punjab, the well known jurist and writer said that the moral of both these incidents is that the army must not be unleashed on the people. A political resolution is the better option. Touching on the two nation theory, Noorani said this plunged Muslims into a crisis not only in India but also in Pakistan. Referring to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as an Indian nationalist and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as a Hindu nationalist, Noorani said Nehru admired Hyderabadi culture, strove even in 1956 to preserve its integrity, and was deeply pained at the atrocities inflicted on Muslims to which Patel was indifferent. During an exclusive interview, A.G. Noorani tells C.R. Gowri Shanker and Mir Quadir Ali that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was responsible for the “Police Action”. He claimed that Patel’s hatred for Hyderabadi culture was the motivating factor behind the orders to the Indian Army to march into the country’s largest princely state. Noorani hits out at Patel by calling him “mean and vindictive” and also criticises Mohd. Ali Jinnah. Excerpts: Q Why did you write Destruction of Hyderabad after six decades of the Police Action? This book is part of a trilogy. The first two parts were Jinnah and Tilak: Comrades in the Freedom Struggle (2010) and Kashmir dispute (May 2013). It mentions what every biographer of the duo suppressed. Q You have titled the book Destruction of Hyderabad. Who destroyed Hyderabad? First and foremost, Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel chose a man who was a notorious Hindu communalist, K.M. Munshi. He was virtually the RSS, Hindu Mahasabha mole in the Congress. That means he didn’t want a settlement. Munshi wanted Hyderabad to be destroyed. He didn’t like Hyderabadi culture. He called it ‘alien’. Q Were some facts about the Police Action suppressed?Absolutely... completely. Hyderabadis didn’t know whether to stay on or go to Pakistan. The Hyderabadi diaspora would not have been in such a situation but for Police Action. Wherever Hyderabadis went, they enriched the societies. Q Why was the Sunder Lal Committee report on the massacre of Muslims suppressed? Who suppressed it?Because Patel was a Hindu nationalist and this report was by a secular man like Sunder Lal. He insulted the man who forwarded the report to him because the Committee was set up by Nehru and Azad. Q Do you think the Police Action could have been avoided? How?Yes, in the same way Operation Blue Star could have been avoided. The economic blockade was beginning to tell. A few months would not have harmed. Q Apart from the Police Action, what was the other option that could have been put in place?There was an effective economic blockade. There were liberal Hyderabadis like Mirza who wanted accession. And with the economic sanction telling, the Nizam would have repudiated these people. They could have waited. Q Hyderabad was the logical third?Yes, Hyderabad was the logical third. On November 1, 1947, Mountbatten gave Jinnah written proposals that if he agreed for a plebiscite in all these three states, the matter could be settled. Jinnah rejected this. He said, “Keep Junagadh and Kashmir and keep off Hyderabad”. That was a fatal mistake. Jinnah not only rejected these proposals he egged on Hyderabad to fight. Had he accepted the proposals, the cold war would have been nipped in the bud. Jinnah was invited to visit Delhi. He could have gone and stayed as a guest of Governor General Mountbatten... he could have gone to the Muslim refugee camps in Delhi... Hyderabad would have survived... perhaps eventually it could have broken up on linguistic lines... the Nizam would not have been humiliated... there would have been no cold war. Everything would have fallen into place.

Annexation of Hyderabad

| Operation Polo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

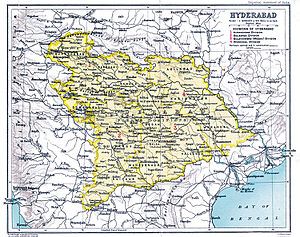

The State of Hyderabad in 1909 (excluding Berar) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 35,000 Indian Armed Forces | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Less than 10 killed[4] | |||||||

Operation Polo was the code name of the Hyderabad "police action" in September 1948,[9] by the then newly independent Dominion of India against Hyderabad State.[10] It was a military operation in which the Indian Armed Forces invaded the Nizam-ruled princely state, annexing it into the Indian Union.[11]

At the time of Partition in 1947, the princely states of India, who in principle had self-government within their own territories, were subject to subsidiary alliances with the British, giving them control of their external relations. With the Indian Independence Act 1947, the British abandoned all such alliances, leaving the states with the option of opting for full independence.[12][13] However, by 1948 almost all had acceded to either India or Pakistan. One major exception was that of the wealthiest and most powerful principality, Hyderabad, where the Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII, a Muslim ruler who presided over a largely Hindu population, chose independence and hoped to maintain this with an irregular army.[14]: 224 The Nizam was also beset by the Telangana rebellion, which he was unable to subjugate.[14]: 224

In November 1947, Hyderabad signed a standstill agreement with the Dominion of India, continuing all previous arrangements except for the stationing of Indian troops in the state. Claiming that it feared the establishment of a Communist state in Hyderabad,[15][16] India invaded the state in September of 1948, following a crippling economic blockade, and multiple attempts at destabilizing the state through railway disruptions, the bombing of government buildings, and raids on border villages.[17][18][3] Subsequently, the Nizam signed an instrument of accession, joining India.[19]

The operation led to massive violence on communal lines, at times perpetrated by the Indian Army.[20] The Sunderlal Committee, appointed by Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, concluded that between 30,000-40,000 people had died in total in the state, in a report which was not released until 2013.[6] Other responsible observers estimated the number of deaths to be 200,000 or higher.[7]

Background[edit]

After the Siege of Golconda by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1687, the region was renamed as Deccan Subah (due to its geographical proximity in the Deccan Plateau) and in 1713 Qamar-ud-din Khan (later known as Asaf Jah I or Nizam I) was appointed its Subahdar and bestowed with the title of Nizam-ul-Mulk by the Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar. Hyderabad's nominal independence is dated to 1724, when the Nizam won a military victory over a rival military appointee.[21] In 1798, Hyderabad became the first Indian princely state to accede to British protection under the policy of Subsidiary Alliance instituted by Arthur Wellesley, and was thus named as the State of Hyderabad.

The State of Hyderabad under the leadership of its 7th Nizam, Mir Sir Osman Ali Khan, was the largest and most prosperous of all the princely states in India. With annual revenues of over Rs. 9 crore,[22] it covered 82,698 square miles (214,190 km2) of fairly homogenous territory and comprised a population of roughly 16.34 million people (as per the 1941 census) of which a majority (85%) was Hindu. The state had its own army, airline, telecommunication system, railway network, postal system, currency and radio broadcasting service.[5] Hyderabad was a multi-lingual state consisting of peoples speaking Telugu (48.2%), Marathi (26.4%), Kannada (12.3%) and Urdu (10.3%). In spite of the overwhelming Hindu majority, Hindus were severely under-represented in government, police and the military. Of 1765 officers in the State Army, 1268 were Muslims, 421 were Hindus, and 121 others were Christians, Parsis and Sikhs. Of the officials drawing a salary between Rs. 600 and 1200 per month, 59 were Muslims, 5 were Hindus and 38 were of other religions. The Nizam and his nobles, who were mostly Muslims, owned 40% of the total land in the state.[23][5]

When the British departed from the Indian subcontinent in 1947, they offered the various princely states in the sub-continent the option of acceding to either India or Pakistan, or staying on as an independent state.[12] As stated by Sardar Patel at a press conference in January 1948, "As you are all aware, on the lapse of Paramountcy every Indian State became a separate independent entity."[24] In India, a small number of states, including Hyderabad, declined to join the new dominion.[25][26] In the case of Pakistan, accession happened far more slowly.[27] Hyderabad had been part of the calculations of all-India political parties since the 1930s.[28] The leaders of the new Dominion of India were wary of a Balkanization of India if Hyderabad was left independent.[14]: 223 [failed verification]

Hyderabad state had been steadily becoming more theocratic since the beginning of the 20th century. In 1926, Mahmud Nawazkhan, a retired Hyderabad official, founded the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (also known as Ittehad or MIM). Its objectives were to unite the Muslims in the State in support of Nizam and to reduce the Hindu majority by large-scale conversion to Islam.[29] The MIM became a powerful communal organisation, with the principal focus to marginalise the political aspirations of the Hindus and moderate Muslims.[29]

Events preceding hostilities[edit]

Political and diplomatic negotiations[edit]

Mir Sir Osman Ali Khan, Nizam of Hyderabad, initially approached the British government with a request to take on the status of an independent constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth of Nations. This request was, however, rejected by the last Viceroy of India, The 1st Viscount Mountbatten of Burma.[30]

At the time of the British withdrawal from India, the Nizam announced that he did not intend to join either new dominion,[31] and proceeded to appoint trade representatives in European countries and to begin negotiations with the Portuguese, seeking to lease or buy Goa to provide his state with access to the sea.[32]

B.R.Ambedkar, the Law Minister in the first independent Indian government considered the state of Hyderabad to be "a new problem which may turn out to be worse than the Hindu-Muslim problem as it is sure to result in the further Balkanisation of India"[33] According to the writer A. G. Noorani, Indian Prime Minister Nehru's concern was to defeat what he called Hyderabad's "secessionist venture", but he favoured talks and considered military option as a last resort. In Nehru's observation, the state of Hyderabad was "full of dangerous possibilities".[33] Sardar Patel of the Indian National Congress, however, took a hard line, and had no patience with talks.[34][35]

Accordingly, the Indian government offered Hyderabad a standstill agreement which made an assurance that the status quo would be maintained and no military action would be taken for one year. According to this agreement India would handle Hyderabad's foreign affairs, but Indian Army troops stationed in Secunderabad would be removed.[3] In Hyderabad city there was a huge demonstration by Razakars led by Syed Qasim Razvi in October 1947, against the administration's decision to sign the Standstill Agreement. This demonstration in front of the houses of the main negotiators, the Prime Minister, the Nawab of Chattari, Sir Walter Monckton, advisor to the Nizam, and Minister Nawab Ali Nawaz Jung, forced them to call off their Delhi visit to sign the agreement at that time.[36]

Hyderabad violated all clauses of the agreement: in external affairs, by carrying out intrigues with Pakistan, to which it secretly loaned 15 million pounds; in defence, by building up a large semi-private army; in communications, by interfering with the traffic at the borders and the through traffic of Indian railways.[37] India was also accused of violating the agreement by imposing an economic blockade. It turned out that the state of Bombay was interfering with supplies to Hyderabad without the knowledge of Delhi. The Government promised to take up the matter with the provincial governments, but scholar Lucien Benichou states that it was never done. There were also delays in arms shipments to Hyderabad from India.[38]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was reported to have warned the then Viceroy Lord Mountbatten "If Congress attempted to exert any pressure on Hyderabad, every Muslim throughout the whole of India, yes, all the hundred million Muslims, would rise as one man to defend the oldest Muslim dynasty in India."[33]

According to Taylor C. Sherman, "India claimed that the government of Hyderabad was edging towards independence by divesting itself of its Indian securities, banning the Indian currency, halting the export of ground nuts, organising illegal gun-running from Pakistan, and inviting new recruits to its army and to its irregular forces, the Razakars." The Hyderabadi envoys accused India of setting up armed barricades on all land routes and of attempting to economically isolate their nation.[3]

In the summer of 1948, Indian officials, especially Patel, signalled an intention to invade; Britain encouraged India to resolve the issue without the use of force, but refused the Nizam's requests to help.[3]

The Nizam also made unsuccessful attempts to seek the intervention of the United Nations.[39]

Telangana Rebellion[edit]

In late 1945, there started a peasant uprising in the Telangana area, led by communists. The communists drew their support from various quarters. Among the poor peasants, there were grievances against the jagirdari system, which covered 43% of land holding. Initially they also drew support from wealthier peasants who also fought under the communist banner, but by 1948, the coalition had disintegrated.[3]

According to the Indian intelligence Bureau Deputy Director, the social and economic programs of the communists were "positive and in some cases great...The communists redistributed land and livestock, reduced rates, ended forced labour and increased wages by one hundred percent. They inoculated the population and built public latrines; they encouraged women's organisations, discouraged sectarian sentiment and sought to abolish untouchability."[3]

Initially, in 1945, the communists targeted zamindars and even the Hindu Deshmukhs, but soon they launched a full-fledged revolt against the Nizam. Starting in mid-1946, the conflict between the Razakars and the Communists became increasingly violent, with both sides resorting to increasingly brutal methods. According to an Indian government pamphlet, the communists had killed about 2,000 people by 1948.[3]

Communal violence before the operation[edit]

In the 1936–37 Indian elections, the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah had sought to harness Muslim aspirations, and had won the adherence of MIM leader Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung, who campaigned for an Islamic State centred on the Nizam as the Sultan dismissing all claims for democracy.

The Arya Samaj, a Hindu revivalist movement, had been demanding greater access to power for the Hindu majority since the late 1930s, and was curbed by the Nizam in 1938. The Hyderabad State Congress joined forces with the Arya Samaj as well as the Hindu Mahasabha in the State.[40]

Noorani regards the MIM under Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung as explicitly committed to safeguarding the rights of religious and linguistic minorities. However, this changed with the ascent of Qasim Razvi after the Nawab's death in 1944.[41]

Even as India and Hyderabad negotiated, most of the sub-continent had been thrown into chaos as a result of communal Hindu-Muslim riots pending the imminent partition of India. Fearing a Hindu civil uprising in his own kingdom, the Nizam allowed Razvi to set up a voluntary militia of Muslims called the 'Razakars'.

The Razakars – who numbered up to 200,000 at the height of the conflict – swore to uphold Islamic domination in Hyderabad and the Deccan plateau[3]: 8 in the face of growing public opinion amongst the majority Hindu population favouring the accession of Hyderabad into the Indian Union.

According to an account by Mohammed Hyder, a civil servant in Osmanabad district, a variety of armed militant groups, including Razakars and Deendars and ethnic militias of Pathans and Arabs claimed to be defending the Islamic faith and made claims on the land.

"From the beginning of 1948 the Razakars had extended their activities from Hyderabad city into the towns and rural areas, murdering Hindus, abducting women, pillaging houses and fields, and looting non-Muslim property in a widespread reign of terror."[42][43]

"Some women became victims of rape and kidnapping by Razakars. Thousands went to jail and braved the cruelties perpetuated by the oppressive administration. Due to the activities of the Razakars, thousands of Hindus had to flee from the state and take shelter in various camps".[43] Precise numbers are not known, but 40,000 refugees were received by the Central Provinces.[3]: 8 This led to terrorising of the Hindu community, some of whom went across the border into independent India and organised raids into Nizam's territory, which further escalated the violence.

Many of these raiders were controlled by the Congress leadership in India and had links with extremist religious elements in the Hindutva fold.[44] In all, more than 150 villages (of which 70 were in Indian territory outside Hyderabad State) were pushed into violence.

Hyder mediated some efforts to minimise the influence of the Razakars.[citation needed] Razvi, while generally receptive, vetoed the option of disarming them, saying that with the Hyderabad state army ineffective, the Razakars were the only means of self-defence available. By the end of August 1948, a full blown invasion by India was imminent.[45]

Nehru was reluctant to invade, fearing a military response by Pakistan. India was unaware that Pakistan had no plans to use arms in Hyderabad, unlike Kashmir where it had admitted its troops were present.[3] Time magazine pointed out that if India invaded Hyderabad, the Razakars would massacre Hindus, which would lead to retaliatory massacres of Muslims across India.[46]

Hyderabadi military preparations[edit]

The Nizam was in a weak position as his army numbered only 24,000 men, of whom only some 6,000 were fully trained and equipped.[47] These included Arabs, Rohillas, North Indian Muslims and Pathans. The State Army consisted of three armoured regiments, a horse cavalry regiment, 11 infantry battalions and artillery. These were supplemented by irregular units with horse cavalry, four infantry battalions (termed as the Saraf-e-khas, paigah, Arab and Refugee) and a garrison battalion.[citation needed]

This army was commanded by Major General El Edroos, an Arab.[48] 55 per cent of the Hyderabadi army was composed of Muslims, with 1,268 Muslims in a total of 1,765 officers as of 1941.[5][49]

In addition to these, there were about 200,000 irregular militia called the Razakars under the command of civilian leader Kasim Razvi. A quarter of these were armed with modern small firearms, while the rest were predominantly armed with muzzle-loaders and swords.[48]

Skirmish at Kodad[edit]

On 6 September an Indian police post near Chillakallu village came under heavy fire from Razakar units. The Indian Army command sent a squadron of The Poona Horse led by Abhey Singh and a company of 2/5 Gurkha Rifles to investigate who were also fired upon by the Razakars. The tanks of the Poona Horse then chased the Razakars to Kodad, in Hyderabad territory. Here they were opposed by the armoured cars of 1 Hyderabad Lancers. In a brief action the Poona Horse destroyed one armoured car and forced the surrender of the state garrison at Kodad.

Indian military preparations[edit]

On receiving directions from the government to seize and annex Hyderabad,[citation needed] the Indian army came up with the Goddard Plan (laid out by Lt. Gen. E. N. Goddard, the Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Command). The plan envisaged two main thrusts – from Vijayawada in the East and Solapur in the West – while smaller units pinned down the Hyderabadi army along the border. Overall command was placed in the hands of Lt. Gen. Rajendrasinghji, DSO.

The attack from Solapur was led by Major General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri and was composed of four task forces:

- Strike Force comprising a mix of fast moving infantry, cavalry and light artillery,

- Smash Force consisting of predominantly armoured units and artillery,

- Kill Force composed of infantry and engineering units

- Vir Force which comprised infantry, anti-tank and engineering units.

The attack from Vijayawada was led by Major General Ajit Rudra and comprised the 2/5 Gurkha Rifles, one squadron of the 17th (Poona) Horse, and a troop from the 19th Field Battery along with engineering and ancillary units. In addition, four infantry battalions were to neutralise and protect lines of communication. Two squadrons of Hawker Tempest aircraft were prepared for air support from the Pune base.

The date for the attack was fixed as 13 September, even though General Sir Roy Bucher, the Indian chief of staff, had objected on grounds that Hyderabad would be an additional front for the Indian army after Kashmir.

Commencement of hostilities[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

Day 1, 13 September[edit]

Indian forces entered the state at 4 a.m.[50] The first battle was fought at Naldurg Fort on the Solapur Secundarabad Highway between a defending force of the 1st Hyderabad Infantry and the attacking force of the 7th Brigade. Using speed and surprise, the 7th Brigade managed to secure a vital bridge on the Bori river intact, following which an assault was made on the Hyderabadi positions at Naldurg by the 2nd Sikh Infantry. The bridge and road secured, an armoured column of the 1st Armoured Brigade – part of the Smash force – moved into the town of Jalkot, 8 km from Naldurg, at 0900 hours, paving the way for the Strike Force units under Lt. Col Ram Singh Commandant of 9 Dogra (a motorised battalion) to pass through. This armoured column reached the town of Umarge, 61 km inside Hyderabad by 1515 hours, where it quickly overpowered resistance from Razakar units defending the town. Meanwhile, another column consisting of a squadron of 3rd Cavalry, a troop from 18th King Edward's Own Cavalry, a troop from 9 Para Field Regiment, 10 Field Company Engineers, 3/2 Punjab Regiment, 2/1 Gurkha Rifles, 1 Mewar Infantry, and ancillary units attacked the town of Tuljapur, about 34 km north-west of Naldurg. They reached Tuljapur at dawn, where they encountered resistance from a unit of the 1st Hyderabad Infantry and about 200 Razakars who fought for two hours before surrendering. Further advance towards the town of Lohara was stalled as the river had swollen. The first day on the Western front ended with the Indians inflicting heavy casualties on the Hyderabadis and capturing large tracts of territory. Amongst the captured defenders was a British mercenary who had been tasked with blowing up the bridge near Naldurg.

In the East, forces led by Lt. Gen A.A. Rudra met with fierce resistance from two armoured car cavalry units of the Hyderabad State Forces. equipped with Humber armoured cars and Staghounds, namely the 2nd and 4th Hyderabad Lancers,[51] but managed to reach the town of Kodar by 0830 hours. Pressing on, the force reached Mungala by the afternoon.

There were further incidents in Hospet – where the 1st Mysore assaulted and secured a sugar factory from units of Razakars and Pathans – and at Tungabhadra – where the 5/5 Gurkha attacked and secured a vital bridge from the Hyderabadi army.

Day 2, 14 September[edit]

The force that had camped at Umarge proceeded to the town of Rajeshwar, 48 km east. As aerial reconnaissance had shown well entrenched ambush positions set up along the way, the air strikes from squadrons of Tempests were called in. These air strikes effectively cleared the route and allowed the land forces to reach and secure Rajeshwar by the afternoon.

The assault force from the East was meanwhile slowed by an anti-tank ditch and later came under heavy fire from hillside positions of the 1st Lancers and 5th Infantry 6 km from Suryapet. The positions were assaulted by the 2/5 Gurkha – veterans of the Burma Campaign – and were neutralised, with the Hyderabadis taking severe casualties.

At the same time, the 3/11 Gurkha Rifles and a squadron of 8th Cavalry attacked Osmanabad and took the town after heavy street combat with the Razakars who determinedly resisted the Indians.[52]

A force under the command of Maj. Gen. D.S. Brar was tasked with capturing the city of Aurangabad. The city was attacked by six columns of infantry and cavalry, resulting in the civil administration emerging in the afternoon and offering a surrender to the Indians.

There were further incidents in Jalna where 3 Sikh, a company of 2 Jodhpur infantry and some tanks from 18 Cavalry faced stubborn resistance from Hyderabadi forces.

Day 3, 15 September[edit]

Leaving a company of 3/11 Gurkhas to occupy the town of Jalna, the remainder of the force moved to Latur, and later to Mominabad where they faced action against the 3 Golconda Lancers who gave token resistance before surrendering.

At the town of Surriapet, air strikes cleared most of the Hyderabadi defences, although some Razakar units still gave resistance to the 2/5 Gurkhas who occupied the town. The retreating Hyderabadi forces destroyed the bridge at Musi to delay the Indians but failed to offer covering fire, allowing the bridge to be quickly repaired. Another incident occurred at Narkatpalli where a Razakar unit was decimated by the Indians.

Day 4, 16 September[edit]

The task force under Lt. Col. Ram Singh moved towards Zahirabad at dawn, but was slowed by a minefield, which had to be cleared. On reaching the junction of the Bidar road with the Solapur-Hyderabad City Highway, the forces encountered gunfire from ambush positions. However, leaving some of the units to handle the ambush, the bulk of the force moved on to reach 15 kilometres beyond Zahirabad by nightfall in spite of sporadic resistance along the way. Most of the resistance was from Razakar units who ambushed the Indians as they passed through urban areas. The Razakars were able to use the terrain to their advantage until the Indians brought in their 75 mm guns.

Day 5, 17 September[edit]

In the early hours of 17 September, the Indian army entered Bidar. Meanwhile, forces led by the 1st Armoured regiment were at the town of Chityal about 60 km from Hyderabad, while another column took over the town of Hingoli. By the morning of the 5th day of hostilities, it had become clear that the Hyderabad army and the Razakars had been routed on all fronts and with extremely heavy casualties. At 5 pm on 17 September, the Nizam announced a ceasefire, thus ending the armed action.[52]

Capitulation and surrender[edit]

Consultations with Indian envoy[edit]

On 16 September, faced with imminent defeat, Nizam Mir Sir Osman Ali Khan summoned his Prime Minister, Mir Laiq Ali, and requested his resignation by the morning of the following day. The resignation was delivered along with the resignations of the entire cabinet.

On the noon of 17 September, a messenger brought a personal note from the Nizam to India's Agent General to Hyderabad, K. M. Munshi, summoning him to the Nizam's office at 1600 hours. At the meeting, the Nizam stated "The vultures have resigned. I don't know what to do". Munshi advised the Nizam to secure the safety of the citizens of Hyderabad by issuing appropriate orders to the Commander of the Hyderabad State Army, Major-General El Edroos. This was immediately done.

Radio broadcast after surrender by the Nizam[edit]

It was Nizam Mir Sir Osman Ali Khan's first visit to the radio station. The Nizam of Hyderabad, in his radio speech on 23 September 1948, said "In November last [1947], a small group which had organized a quasi-military organization surrounded the homes of my Prime Minister, the Nawab of Chhatari, in whose wisdom I had complete confidence, and of Sir Walter Monkton, my constitutional Adviser, by duress compelled the Nawab and other trusted ministers to resign and forced the Laik Ali Ministry on me. This group headed by Kasim Razvi had no stake in the country or any record of service behind it. By methods reminiscent of Hitlerite Germany it took possession of the State, spread terror ... and rendered me completely helpless."[53]

The surrender ceremony[edit]

According to the records maintained by the Indian Army, General Chaudhari led an armoured column into Hyderabad at around 4 p.m. on 18 September and the Hyderabad army, led by Major General El Edroos, surrendered.[54]

Communal violence during and after the operation[edit]

There were reports of looting, mass murder and rape of Muslims in reprisals by Hyderabadi Hindus.[20][43] Jawaharlal Nehru appointed a mixed-faith committee led by Pandit Sunder Lal to investigate the situation. The findings of the report (Pandit Sunderlal Committee Report) were not made public until 2013 when it was accessed from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi.[20][55]

The Committee concluded that while Muslim villagers were disarmed by the Indian Army, Hindus were often left with their weapons.[20] The violence was carried out by Hindu residents, with the army sometimes indifferent, and sometimes participating in the atrocities.[3]: 11 The Committee stated that large-scale violence against Muslims occurred in Marathwada and Telangana areas. It also concluded: "At a number of places members of the armed forces brought out Muslim adult males from villages and towns and massacred them in cold blood."[20] The Committee generally credited the military officers with good conduct but stated that soldiers acted out of bigotry.[3]: 11 The official "very conservative estimate" was that 27,000 to 40,000 died "during and after the police action."[20] Other scholars have put the figure at 200,000, or even higher.[8] Among Muslims some estimates were even higher and Smith says that the military government's private low estimates [of Muslim casualties] were at least ten times the number of murders with which the Razakars were officially accused.[56]

Patel reacted angrily to the report and disowned its conclusions. He stated that the terms of reference were flawed because they only covered the part during and after the operation. He also cast aspersions on the motives and standing of the committee. These objections are regarded by Noorani as disingenuous because the commission was an official one, and it was critical of the Razakars as well.[8][57]

According to Mohammed Hyder, the tragic consequences of the Indian operation were largely preventable. He faulted the Indian army with neither restoring local administration, nor setting up their own military administration. As a result, the anarchy led to several thousand "thugs", from the camps set up across the border, filling the vacuum. He stated "Thousands of families were broken up, children separated from their parents and wives, from their husbands. Women and girls were hunted down and raped."[58]

According to the communist leader Puccalapalli Sundarayya, Hindus in villages rescued thousands of Muslim families from the Union Army's campaign of rape and murder.[59][non-primary source needed]

Hyderabad after integration[edit]

Detentions and release of people involved[edit]

The Indian military detained thousands of people during the operation, including Razakars, Hindu militants, and communists. This was largely done on the basis of local informants, who used this opportunity to settle scores. The estimated number of people detained was close to 18,000, which resulted in overcrowded jails and a paralysed criminal system.[3]: 11–12

The Indian government set up Special Tribunals to prosecute these. These strongly resembled the colonial governments earlier, and there were many legal irregularities, including denial or inability to access lawyers and delayed trials – about which the Red Cross was pressuring Nehru.[3]: 13–14

The viewpoint of the government was: "in political physics, Razakar action and Hindu reaction have been almost equal and opposite." A quiet decision was taken to release all Hindus and for a review of all Muslim cases, aiming to let many of them out. Regarding atrocities by Muslims, Nehru considered the actions during the operation as "madness" seizing "decent people", analogous to experience elsewhere during the partition of India. Nehru was also concerned that disenfranchised Muslims would join the communists.[3]: 15–16

The government was under pressure to not prosecute participants in communal violence, which often made communal relations worse. Patel had also died in 1950. Thus, by 1953 the Indian government released all but a few persons.[3]: 16

Overhaul of bureaucracy[edit]

Junior officers from neighbouring Bombay, CP and Madras regions were appointed to replace the vacancies. They were unable to speak the language and were unfamiliar with local conditions. Nehru objected to this "communal chauvinism" and called them "incompetent outsiders", and tried to impose Hyderabadi residency requirements: however, this was circumvented by using forged documents.

The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and

the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948-56

Original citation: Sherman, Taylor C.

(2007)

Abstract

This article explores the impact of the police action

and the anti-communist struggle in Hyderabad on the formation of the Indian

state in the first years after independence. Because of its

central location and diverse cultural heritage, the absorption of the

princely state of Hyderabad into the Indian Union was an important goal for

Nehru’s government. But the task of bringing Hyderabad into the Union was not

an easy one.

As it entered Hyderabad, the government of independent

India had to come to terms with the limitations of the police, military

and bureaucracy which it had inherited from the colonial state.

As it took over the governance of the state, it had to

find ways to manage relations between Hindus and Muslims, even as the social

order was being transformed. And it had to fight communism in the Telangana

region of the state, whilst trying to ensure the loyalty of its new citizens.

This article examines the ways in which India’s first

government confronted these complex problems. The following pages argue that

these early years must be seen as a time of great dynamism, rather than as a

period of stability inherited from the colonial state.

There is near consensus amongst scholars of

postcolonial India that, at least in retrospect, the Nehruvian period was one

of relative calm and stability.

According to this line of thought, independence

did herald change in India, including the introduction of democracy with

universal suffrage and a constitution with a charter of fundamental rights, but

the trauma of partition, the war over Kashmir and the integration of the

princely states, ‘ensured that precisely those traits of the Raj which Indian

nationalists had struggled against were now reinforced’.

The police, military and bureaucracy inherited from

the colonial regime, it is agreed, enabled the Congress-led government to

‘enforce central authority’, and to ensure stability in a unified Indian

state.

The following pages challenge this view by examining

the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad into the Indian Union. It is

argued that this view posthumously invests the colonial state/early

postcolonial state with qualities it did not have.

The idea that the colonial state acted as a monolithic

machine to stamp out dissent and disorder where it pleased is unsustainable.

Central policy was often fraught with contradictions. Institutions, especially

the police, courts and prisons, were often overwhelmed by the work thrust upon

them during times of unrest.

Tensions between the centre and local administrators

frequently erupted, as officers used their position as ‘the man on the spot’ to

act contrary to orders or to justify committing acts of violence against the

subject population.

Taken as a whole, therefore, the colonial state

was often either weak and inefficient or extraordinarily violent and

ineffective.

By taking the absorption of Hyderabad as a case study,

this work examines the ways in which the new government coped with its

inheritance.

Hitherto, the story of the integration of the princely

state of Hyderabad into the Indian Union has been told from a number of

relatively parochial perspectives.

There have been personal stories of hardship and

bravery during the conflict; detailed analyses of the tortured negotiations

between the Indian government, the Nizam of Hyderabad and the British; clinical

accounts of the military operations; and histories of the communist

Telangana movement in the territory. None of these accounts, however, have

examined the impact of the integration of Hyderabad on the formation of

the state in newly independent India.

The absorption of Hyderabad provides an

excellent study of the nature of the postcolonial Indian state for three

reasons.

First, Hyderabad had been part of the calculations of

all-India political parties at least since the 1930s. The territory was

therefore a vital part of the self-image of newly-independent India. Secondly,

it was the Ministry of States, part of the central government in Delhi, which

assumed overall responsibility for the integration of the former princely

states.

After the police action of September 1948, the

Hyderabad regime was virtually disbanded. As a result, the new authorities had

relative freedom to shape the new territory as they pleased.

Finally, as Hyderabad was brought into the Union,

police, military and members of the bureaucracy were drafted in from the rest

of India to rebuild Hyderabad. One can therefore use the case of Hyderabad not

only to try to understand the ‘mind’ of the central government, but to examine

the extent to which policies designed by the centre were successfully

implemented on the ground.

When they assumed power in Hyderabad, the new Indian

government faced an array of questions the answers to which would impact the

shape and character of the new nation-state as a whole. These included, how to

deal with the limitations of the military, police, and bureaucracy which they

had inherited; how to frame the new constitution to protect the integrity

of the country; how to manage relations between Hindus and Muslims, whether in

the bureaucracy or in the population; and how to fight communism and ensure the

loyalty of their new citizens.

This article explores these questions in three

sections.

First, it situates the princely state of Hyderabad at

the geographic, economic and cultural heart of the sub-continent, and locates

the territory in the vision of India imagined by the British and their

Indian successors.

Secondly, it analyses the ways in which the Indian

authorities addressed the question of relations between Hindus and Muslims

after the fall of the Muslim-led government of the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Finally, it turns to the ways in which the Indian

army, and then the civilian authorities, confronted the communist

Telangana movement in the eastern part of the state. It is argued below that,

in the years shortly after independence, India’s internal character had yet to

be set in stone, and the experience of the integration of Hyderabad reflects

the vibrancy and uncertainty of the early Nehruvian period.

Hyderabad and the Indian Union

The history of the awkward place of the princely

states in the transfer of power negotiations is well known. On the

eve of independence, several large states, including Hyderabad, had declined to

join either India or Pakistan.

Each state presented its own unique problems, but the

Government of independent India believed that the accession of Hyderabad to the

Indian Union was ineluctable.

As early as June 1947, Nehru had warned he would

‘encourage rebellion in all states that go against us’.10 In the new Indian

Government, the accession of the subcontinent’s second largest princely

state was viewed as a foregone conclusion because Hyderabad could not be

independent except in name, given its geographical position.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, India’s Home member and

Minister for States remarked, ‘Hyderabad is, as it were, situated in India’s

belly. How can the belly breathe if it is cut off from the main

body?

In the summer of 1948, as India’s statesmen,

especially Patel, began to hint of an invasion, the British encouraged India to

avoid using force, but repeatedly declined the Nizam’s requests to intervene on

his behalf.

In the months preceding independence, however, Nizam

Mir Osman Ali Khan Bahadur had refused to accede to either India or Pakistan.

He attempted, instead, to manoeuvre his state towards independence, from where

he could negotiate an alliance with India, rather than amalgamation into India.

To avoid accession, the Nizam’s government had signed

a Standstill Agreement with the Government of India. The accord provided that

relations between the state and the Indian Union would remain for one year as

they had been prior to independence.

India would handle Hyderabad’s foreign affairs, but

Indian Army troops stationed in Secunderabad would be removed. Soon after the

agreement had been struck, however, each side began to accuse the other of

violating its terms.

The Nizam alleged that the Indian government was

imposing an informal embargo by using its control over railways leading into

the state to deny the territory vital goods, especially arms and medical

supplies.

India claimed that the government of Hyderabad was

edging towards independence by divesting itself of its Indian securities,

banning the Indian currency, halting the export of ground nuts, organising

illegal gun-running from Pakistan, and inviting new recruits to its army and to

its irregular forces, the Razakars. These moves were regarded in Delhi as part

of a ‘comprehensive plan to break up the economic cohesion of India.’

The situation in Hyderabad in 1948

While the Nizam attempted to manoeuvre himself towards

independence, the internal situation in the territory was deteriorating. The

state had been crippled by communist insurgents on the one hand, and forces

loyal to the Nizam of Hyderabad on the other.

To a limited extent, Congress volunteers engaged

in satyagraha had contributed to the internal disorder by disrupting courts,

filling jails, and engaging in sabotage with the aim of convincing the Nizam to

join the Indian Union.

As stories of the conflict in the state spread in

India, and refugees fled into the surrounding Indian provinces, the Government

of India concluded that the unrest threatened to undermine peace in

the whole of India.

When, in 1947, the authorities in Hyderabad refused to

accede to either dominion, many opposition parties in the state called for the

Nizam to join the Indian Union.

The Congress launched a satyagraha, and encouraged

students to leave schools, and lawyers to boycott courts. More radical members

of the Hyderabad State Congress planned acts of sabotage, organised raids

against government property and communications, and authorised their members to

take action in ‘self-defence’, with weapons if necessary.

According to an Indian government note in March

1948, 'the educational institutions function no more, the law courts are barren

and the commercial life is shattered.' As many as 21,000 congressmen were said

to have been arrested.

However, the Hyderabad State Congress Party was

divided organisationally along regional lines, and ideologically between

socialists and liberals; its impact on the internal situation in the state,

therefore, was more limited than that of the communists.

The fight between the communists and forces loyal to

the Nizam, by contrast, was characterised in the spring of 1948 as ‘a people's

revolt on the one side and fascist orgy and anarchy on the other’. Its roots

were in the insurgency begun in 1944-1945 in the Nalgonda and Warangal

districts, known as the Telangana area, in the east of the territory.

Forces loyal to the Nizam of Hyderabad sought to

repress this communist movement. These forces comprised of police and

military as well as local members of the Razakars.

The Razakars

The Razakars, headed by Kasim Razvi, were a

paramilitary organisation comprised of volunteers who were said to be

as enthusiastic as they were undisciplined Razvi and his volunteers

were associated with the Majlis-i-Ittehad-ul-Muslimein, a political party with

considerable influence over the Nizam and dedicated to maintaining Muslim

rule in Hyderabad.

Both communists and forces loyal to the Nizam employed

brutal measures to strike against their enemy and intimidate villagers into

collaboration.

According to a pamphlet that the Government of India

had drawn up for public consumption, between 15 August 1947 and 13 September

1948, the communists had murdered 2000 people, attacked 22 police outposts,

destroyed village records, manhandled 141 village officials, seized 230 guns,

eight revolvers and one rifle, looted or destroyed paddy worth Rs70,000, robbed

cash and jewellery worth Rs10,43,668, and destroyed 20 customs outposts.

While the primary fight up until early 1948 had been

between the communists and the Nizam’s forces, in May 1948, the Nizam and urban

members of the communist party struck an improbable tactical alliance against a

common enemy, the ‘bourgeois’ Indian Union.

According to the agreement, which claimed to bolster

the fight for the independence of Hyderabad, the Nizam amnestied communists

from jails, cancelled outstanding arrest warrants and lifted the ban

on the party.

During the summer of 1948, the Razakars continued to

seek out and eliminate the enemies of the regime. They targeted not only

Hindus, but Muslims whose loyalty was in doubt. As it became clear that

negotiations with the Indian Union were stalemated, they also courted

confrontation with Indian forces. Their raids against trains and villages in

Madras, the Central Provinces (CP) and Bombay raised panic in these

provinces.

In July, Razakars killed six Indian Army troops in an

ambush near the Indian enclave of Nanaj. Equally, there were allegations

that Indian troops crossed Hyderabad’s borders as they gave chase to

Razakars.

The Government in Delhi concluded that the increasing

influence and violence of these unruly volunteer paramilitaries proved that the

Nizam had lost control over his own territory.

These battles threatened to spill into Union territory

in more than one way. First, refugees fleeing the disorders escaped into Indian

territory to form large camps in the provinces of Madras and Bombay. Some

estimates put the number of refugees at 40,000 in CP alone.

Secondly, though the fault lines in the conflict did

not run neatly along religious lines, the perceived ‘communal’ nature of the

fighting threatened to revive Hindu-Muslim tensions in India.

The Nizam’s government tended to privilege a few

thousand Muslims, leaving an underclass of poor Muslims. Nationalist Muslims in

the State tended to oppose the Nizam, while, as far away as Delhi, the

Socialist Party enrolled Muslim volunteers to agitate against the Nizam.

At the same time, the Depressed Classes Association

and Depressed Classes Conference in Hyderabad had joined hands with the

Nizam in June 1947 to fight against incorporation into the Indian Union,

because they believed accession would entail domination by caste Hindus.

The structure of rule in the state, however, where a

predominantly-Muslim government and gentry held power over large numbers of

disadvantaged, of whom the majority were Hindus, appeared to divide the

population along religious lines.

And some political parties took advantage of this.

Since the war, the All-India Hindu Mahasabha had used this government structure

to gather support for their organisation.

In 1941 they began to keep a record of all, ‘tyrannous

and political injustices and unfairness on the Hindus in all Provinces and

particularly under Muslim administration and Muslim states.’31 Hyderabad was no

exception.

As the violence of the Nizam’s forces increased in

Hyderabad, Hindu nationalists called on Muslims throughout India ‘to give proof

of their loyalty to the Indian Union,‘ by opposing the Nizam’s regime.33

Clearly, the subtleties and complexities of the Hyderabad situation were

being folded into all-India communal politics.

The Government of India, therefore, concluded that the

unrest in Hyderabad threatened to destabilise ‘the communal situation in the

whole of India’.

In the volatile international situation in South Asia

in the year following independence, Nehru had been reluctant to use force to

bring Hyderabad into the Indian Union.

The Indian economy was suffering a crisis of

inflation, accompanied by a panic in the gold market, which impelled the

Government of India to re-impose controls on textiles and other essential

commodities.

In addition, the autumn of 1948 was a tense time for

the militaries on the subcontinent. Pakistan had admitted that its troops

were present in Kashmir, and Nehru was writing of being at war with its

neighbour, albeit an undeclared one.

India feared that any move against Hyderabad would

prompt a military response from Pakistan. Though Pakistan had no plans to

protect Hyderabad with arms, India did not know this. Moreover, the new

government in India was trying to calm tensions after the violence of

partition, and struggling to provide for millions of refugees.

The situation in Hyderabad, they concluded, must be resolved before it adversely affected India’s internal and international security.

On 13 September 1948, therefore, the Government of

India declared a state of emergency, and sent its troops into Hyderabad

State.

During the ‘police action’, the Indian Army entered

Hyderabad with the objective of forcing the Nizam to re-install Indian troops

in Secunderabad to allow them to restore order in the state. The Nizam

surrendered in four days, and the Government of India

appointed Major-General J.N. Chaudhuri as Military Governor. Delhi decided that

the Nizam could retain his position as Rajpramukh, though law-making and

enforcement power rested with the Military Governor.

Hindu-Muslim relations and the character of the

new Hyderabad State

Once they had seized control of the territory,

the new Military Governor, Major General Chaudhuri, the Chief Civil

Administrator, D.S. Bakhle, and the Government in Delhi had to ask themselves

what character and composition they wished the new Hyderabad state to have.

This question involved a number of different elements.

First, to what extent would those who took part in

violence before and during the police action be punished for their activities?

Secondly, how far would the Muslim-dominated administration in the state be

altered? Finally, what role would the Congress Party have in the new state?

Given that each of these questions impacted Hindu-Muslim relations, Nehru felt

that the decisions which they made in Hyderabad would be seen as the touchstone

of the Indian government’s minority policy.

Before the invasion of Hyderabad, Nehru’s primary

concern was to normalise Hindu-Muslim relations there and in the rest of the

country. He wrote to Patel that, after the problem of the Razakars, all other issues

were ‘relatively secondary’.

Before the first Indian troop set foot in Hyderabad,

there was much uncertainty over whether the police action would provoke an

adverse reaction amongst Muslims in India.

In the state’s surrounding provinces, therefore,

provincial governments detained dozens of Muslims, including Members of the

Legislative Assembly, for ‘security reasons’, on the grounds that their

sympathies with Hyderabad might spur them into inciting unrest.

As troops marched into the state, many Muslims in

India lent their support to the police action, however. Prominent Muslims in

Delhi publicly welcomed the Government of India’s choice to come to the aid of

the ‘innocent masses’ threatened by the Razakars, and appealed for calm.

In the event, there was no trouble in India during the

five days of the police action. Indeed, before reports emerged of the fighting

within the state, Nehru ventured to declare that Hyderabad had

'suddenly opened out a new picture of communal peace and harmony.'

Quickly, however, stories began to seep out of

large-scale violence within the territory in the immediate aftermath of the

police action.

It is unclear exactly what happened between the people

of Hyderabad, the members of the falling regime, and the invading forces during

and immediately after the police action, but it appears that there was

widespread bloodshed as the population took the opportunity to commit acts of

violence against the Razakars and other Muslims.

Two prominent nationalists, Pandit Sunderlal and

Qazi Abdulghaffar prepared a report on the situation after Nehru appointed them

to tour the state and assess the extent of the destruction, but the original

was suppressed and only scraps of it remain.

They recorded that after 13 September, there had

been a widespread anti-Muslim purge, which had occurred primarily in the

Marathwada and Telangana areas.

What evidence is available suggests that Hindu

residents as well as some members of the Army attacked persons and property in

the weeks after the police action began.

Conservative estimates suggest that 50,000

Muslims were killed.46 Others claim several hundred thousand died. Indian

troops in some places remained aloof from these activities, in others, they were

implicated in them.

Sunderlal and Abdulghaffar concluded that, ‘In

general the attitude of the military officers was good but the soldiers showed

bigotry and hatred.’49 The invasion of Hyderabad had not heralded a new era

of communal harmony in the territory. Instead, the main task of the new

authorities in the state was to cope with the aftermath of the turmoil.

In order to depose the existing regime and to contain

the unrest, the Government of India’s police and military authorities had

detained Razakars, Hindu militants, communists and many others more loosely

connected with the general upheaval.

According to their own figures, the military and

police detained over 13,000 Muslims, plus several hundred Arabs and Pathans,

who were associated with the Razakars and the Nizam’s irregular forces. Another

several thousand Hindus were jailed after having been implicated in the

post-police action reprisals against Muslims.

Many communists were also detained. But it is

clear that, with their limited knowledge of the local situation, the invading

forces simply jailed thousands of suspects without real knowledge of their

activities.

The police and military were captive to local

informants, who took advantage of the situation to have their political enemies

imprisoned. Indeed, many of the difficulties which the colonial

regime had faced when confronting large-scale communal unrest also

affected the early postcolonial government: the police and military were

disposed to make mass arrests in order to restore order, and to think about

prosecution only after the event.

But court cases often simply provided another arena

for the conflict, and the government came under political pressure to release

those detained.

Having imprisoned an estimated 17,550 people as

they entered the territory, the Government of India was left with the questions

of what to do with all the prisoners rounded up in the upheaval, and how to

relieve the problem of over-crowded jails.

In Hyderabad, the Government of India inherited a

criminal justice system which had been paralysed by the conflict, and could not

process any significant number of cases.

This meant that, just as in British India,

politics came to determine who was subjected to formal punishment, and who

escaped.

Of course, many of the political claims of the

Nehru government were different from those of the British: they were concerned

not to spend money on expensive legal proceedings which could otherwise be used

for development projects; and they were sensitive to the importance of

political parties in a democratic age.

For their part, many members of the public

remained constant in their insistence that, when the government punished

participants in communal violence, this only worsened relations between

those communities who were perceived to be at loggerheads with one

another.

For these reasons, though thousands were originally

detained, only a few exemplary persons remained in jail by 1953.

Given the volume of cases, the military regime decided

to prosecute only those ‘who indulged in the worst kind of atrocities’. In the

six months following the Nizam’s defeat, therefore, the government released

over 11,000 Muslims without trial because no incriminating evidence against

them existed.

They also deported some 2000 Arabs back to Aden

and a similar number of Pathans to ‘other parts of India’.

Major-General Chaudhuri and his administration

planned to prosecute the remainder of those detained. Accordingly, shortly

after the proclamation of the State of Emergency, the Government of India

propounded a Special Courts Order to dispense with the large numbers of persons

in jail. In a word, the order was designed to process cases speedily.

To this end, it relaxed the standards of written

evidence by requiring only summaries of the evidence rather than full accounts;

it made it impossible for an accused to deliberately delay proceedings,

e.g. by hunger striking; and, at first, it provided for no right to appeal to

higher courts. This latter provision was amended in October 1949, to allow

appeals to the High Court for major offences.

T here

was no mention either way as to access to a lawyer, and it appears that

while

some of the accused obtained counsel, others declined or were denied access

to one. The ordinance strongly resembled those which had been passed by

the colonial government during the twentieth century. For example, it

incorporated the lessons which the British had learnt by making it impossible

for a defendant to delay a case by hunger striking.

As the trials made halting progress,

thousands languished in jails waiting for the police to finish

investigating their cases or for the courts to begin their trials.

By April 1949, appeals for an amnesty were gaining

volume. Thirteen Urdu

newspapers jointly asked the government to free

Muslims who had been imprisoned

‘on mere suspicion’ and had yet to stand trial. The

editors suggested that these men

had suffered in jail long enough, and that their

continued detention would serve no

good purpose. To release them would help create a

‘harmonious atmosphere’ in the

state, and it would foster the minority community’s

confidence in the government.60

Similarly, Swami Ramandanda Tirtha, leader of the

Congress Party in the state,

agreed that the institution of cases for events which

had occurred nine months before

was ‘causing great discontent’.

The constraints of governance in a democratic state

had an impact in three rather

contradictory ways on the decisions which the

government made about these

prisoners.

First, as these men had been detained for several

months without trial, the

International Committee for the Red Cross was pressing

Nehru to see that those

detained were either prosecuted or released.

Nehru had long since realised that the eyes of

the world were on Hyderabad and wished to prove that the new Indian Government

could be balanced in its approach to both Hindus and Muslims.

Secondly, it was the widely held opinion amongst the

new rulers of the state that the communist and ‘communalist’ parties in

the state remained popular because the state Congress Party was weak.

Chaudhuri, therefore, hoped that the release of prisoners would

‘rehabilitate the prestige of the Hyderabad State Congress’ Party in the

eyes of the public in Hyderabad, and improve relations between the state

and national sections of the party.64 Even so, there could be no general

amnesty because the Military Governor still wished to prosecute prominent

Razakars such as Kasim Razvi.

When the government of Hyderabad, in consultation with

the centre, weighed these

arguments, they knew that any policy adopted could not

be seen to favour either

Hindus or Muslims. The new government convinced itself

that equal blame did attach

to each community.

In Major-General Chaudhuri’s words, ‘in political

physics, Razakar action and Hindu reaction have been almost equal and

opposite’. Thus, when it was decided to free all Hindus and to institute a

programme for the review of Muslim cases with an aim to gradually letting

many out of jail, the government preferred that the policy be given no publicity. Releases

were staggered and former prisoners made to report periodically to the police.

Because prosecutions of either Hindus or Muslims in

cases of ‘communal’ violence tended to elicit allegations of bias, any

cases which were brought to court had to be designed to minimise ethnic

tensions.

Thus, Kasim Razvi and four of his associates were

prosecuted for the alleged murder of a fellow Muslim, Shoebullah Khan.

The victim, a nationalist journalist who had

opposed the Razakars, was killed on 22 August 1948. His murder attracted

public interest, though only after the police action had begun. The Bombay

Chronicle described the journalist as ‘a brave young man’ for refusing to

bow to the will of the Ittehad-ul-Muslimein.

The paper went on to declare Shoebullah ‘a martyr

in the cause of the people.’69 Though a Special Tribunal found Razvi and

his cohorts guilty, they were acquitted in the High Court.

The same men stood accused in the Bibinaga

Dacoity Case, which ran simultaneously with the Shoebullah Khan case. In the

former, it was alleged that, when passing through Bibinagar station in a

train, the accused had shouted 'Shah-e-Osman zindabad', but the people in

the station had replied with the nationalist slogan ‘Mahatma Gandhi

ki jai’.

The accused then disembarked, and proceeded to burn

down a house, and beat and rob those in the vicinity of the

station.70 In this case, the High Court upheld the Special Tribunal’s

guilty verdict, and the men were sentenced to imprisonment. It

was believed that if this type of case were chosen then the prosecutions

would be more likely to inspire in the public feelings of pure abhorrence

or deep nationalism, rather than enmity between Hindus and Muslims.

As news of the convictions of Razvi and his men

reached the public, prominent politicians again pressed Nehru to

show generosity to the Muslims of Hyderabad.The Prime Minister was sympathetic.

Hyderabadi Muslims, he wrote to Patel, exemplified a unique ‘and rather

attractive culture’, and were ‘very much above the average’.

In essence, Nehru argued that Muslim prisoners in

Hyderabad were not criminal types, and therefore did not merit punishment.

Instead, their behaviour in the summer and autumn of 1948 was analogous to

the ‘madness’ that seized ‘decent people’ in the country during partition.

Many of those guilty of partition violence remained free in India and

lived ‘as respected citizens.’

By this logic, if the crimes of partition

could be buried, so could those of Hyderabad’s accession. Nehru

also warned that if a gesture of ‘friendliness’ were not offered ‘to those

who are down and out and full of fear’ these disenfranchised Muslims could

join forces with the communists. Finally, the Prime Minister argued, in a

developing state the money spent on prosecution could have ‘brought rich

results if spent on constructiveactivities in Hyderabad.’74

When Nehru first voiced these arguments, Patel

demurred. He was convinced that

the promise of penal action against criminals had

helped restore law and order, and

that if that promise were not fulfilled, it would

signal the government’s partiality for

Muslims and would endanger the peace in the state.75

By the time the cases of

Kasim Razvi and of the ex-ministers of the Nizam’s

regime had wound their way

through the judicial system, Patel had passed away and

elections were about to be

held under a much improved political atmosphere in the

state. In January 1952, all

ex-Ministers were released; only Kasim Razvi and a few

members of the Nizam’s

regime who had been involved in the most notorious

cases remained in prison.76

In the end, only a handful of symbolic Razakars were punished with formal

imprisonment. Just as its colonial predecessor had

been, the Indian government

faced administrative constraints which precluded the

use of the ordinary judicial

system to dispose of every case arising out of large scale violence.

The police and military, lacking real intelligence or familiarity with the territory, jailed thousands

without obvious cause, and without labouring to find

one. Courts, even special

tribunals, were unable to work through the cases at a reasonable speed.

Pleas for amnesty inevitably arose in circumstances in which the members of the public

believed that people were being detained unfairly for

protracted periods. Political

considerations, therefore, determined the futures of

those who found themselves in

jail.

Intimately tied to these issues was the question of

the Hindu-Muslim balance in the

services. The well-known rivalry between Patel and

Nehru was crucial in this respect,

as Patel often ran the States Ministry without as much

consultation with Nehru’s

Cabinet as the Prime Minister would have preferred.77

Before the invasion, Nehru

had presided over a meeting in which it was decided

that, in order to be generous to

the Nizam and to create a positive impression on the

other princely states, the

military regime ought to change as little as possible in Hyderabad.

Dramatic administrative and policy changes in the territory were to wait for a democratically-elected government.78 At other levels of administration, however, divergent ideas took hold. The new authorities in Hyderabad attempted to adjust the ethnic balance in the executive, police and administrative services, where Muslims predominated.

To this end, they dismissed over a hundred officers,

from the Chief Secretary to low-

level police personnel. 79 They also detained many of

those local officers who were

suspected of participating in the violence which

accompanied the police action. In

addition, they attempted to reduce the number of

Muslims working in the civil service

or sitting as judges through forced retirement, or transfer from the state. They

adopted a policy of not hiring new Muslims in the

services. The civilian administration

under Vellodi continued this policy.80 And the

government introduced in June 1950

under a scheme of diarchy had similar ideas.81

To replace those dismissed, they drafted in junior

officers from Bombay, CP and

Madras. This created greater difficulties, however, as

many of the new officers were

not only inexperienced, but were also unable to speak

the languages of the people

under their jurisdiction, and were unfamiliar with

local conditions.82 This left the

administration generally, and the criminal justice

system in particular, unable to

function efficiently or effectively. The Prime

Minister objected to these schemes on

the grounds that they were both inspired by ‘communal’

chauvinism and impractical

because they brought in incompetent outsiders.83

Nehru, along with many

Hyderabadis, called for qualified Hyderabad residents

to fill vacant posts. However,

the people taking the reigns of power in Hyderabad

were able to circumvent these

orders by falsifying residency documents.84 Thus, the

answers which were found to

the question of the ethnic composition of the services

were neither similar, nor co-

ordinated. It is clear that the new Indian government

in Delhi, like its British

predecessor, had to contend with competing visions of

the state. These visions were

not identical to those present before 1947, but they

were a mark of the continued

inability of the centre to elicit discipline and

obedience from the individuals it

employed.

The Congress party in Hyderabad

The final question facing the new authorities in

Hyderabad was what the role of the

Congress Party in the state ought to be. Initially,

the answer seemed relatively

straightforward to the government in Delhi.

Congressmen at the head of the

Government of India wished the Hyderabad State

Congress Party to guide the future

of the state. To some extent this decision can be

explained by the supposed

ideological affinity between the local and the

national party. Technically, the

Hyderabad State Congress had not been part of the

all-India party because

affiliations with outside organisations had been

banned under the Nizam.

Hyderabad’s Swami Ramananda Tirtha, however, had

participated in the non-

cooperation movement in Sholapur, and later made

frequent visits to Gandhi. Tirtha

often consulted him on matters of policy, though the

two did not always agree.85 In

addition, the all-India party had contributed to the

Congress satyagraha in the state in

1938.86 Moreover, the Hyderabad State Congress was

also one of the few political

organisations which was not confined to a single

linguistic group, and which

attempted to span the entire state. It would be easier

to work with a single

organisation rather than with the several linguistic

parties.

At the time, however, the Hyderabad State Congress had

been in existence for little

more than a decade, and had operated as no more than a

token institution before

1946. It suffered from organisational shallowness and

internal divisions.87 If it were to

take power successfully, the Hyderabad State Congress

Party would need all the

help it could get from the national party. To this

end, when they took over the

governance of the state, the Indian authorities

ordered the release of all

Congressmen who had landed in Hyderabad’s jails during

their campaign of

satyagraha and sabotage before the police action.

Before the release, there was

some debate as to whether those who had committed

crimes of violence should be

freed. In the event, Congressmen accused of violent

crimes were let out, while

communists were kept in jail, whether their crimes

involved violence or not.88 Under

these orders, the Government of India released 1222

out of 1736 detenus, and 7893

out of 9218 political prisoners.89

Taylor C. Sherman

20

The situation was far more fluid than had been

anticipated, however. As the military

and police attempted to restore order by arranging

prosecutions against those who

had partaken in the violence, many Congressmen ended

up back in jail. The Military

Governor reported that one faction in the party, ‘has

given information against the

members of the other groups for having been concerned

in the commission of

atrocities after police action.'90 It became clear

that the fissures within the Hyderabad

State Congress would not be easy to repair. Nehru met

with Congressmen in the

state to persuade them to bury their differences in

the interests of their country.91

V.P. Menon and Sardar Patel, repeatedly pressed the

divergent blocs in the party to

adopt a ‘united approach’, but their ‘bickering’ and

‘mud flinging’ continued

unabated.

Thus, though the Government of India

originally had intended to

establish a constituent assembly in Hyderabad, and to

transfer power to a civilian

government composed of Hyderabadis, within a few

months of the police action, both

objectives were soon shelved. The government in Delhi

refused to hand power to

democratically-elected representatives when the

Hyderabad State Congress

remained in ideological and organisational disarray.93

It therefore orchestrated a

more gradual transfer of power, and did not sanction

state-wide elections until 1952.

If the state comprises not only policy, but

institutions and individuals, it is difficult to

draw a clear and simple picture of the Indian state

during the first months after the

police action because these three levels seem to be

pulling in different directions.

Policy coming from the Government of India level was

clearly concerned to appear

even-handed in its punishment of participants in the

violence which surrounded the

deposal of the Nizam’s regime.

Nehru, at least, was

also keen to avoid making

drastic changes to state institutions. But as they

took control of Hyderabad, the new

Indian government found itself with poor institutions

and independently-minded local

officers. As a result, the composition of the

administration in Hyderabad was changed

significantly, and Muslims tended to be disenfranchised during this period. The nature of politics in a democratic state also affected policy, for the centre’s decisions

were designed to improve the stature of the Congress

party, and to appeal to certain

members of the electorate. But there were others who

were not so easily pleased,

and it is to the communists that we now turn.

The communist insurgency and the making of the new

state

When they arrived in Hyderabad, the Indian military

found that the communists had

done great damage to the structures of government in

the Telangana region, but that

they had also introduced reforms on an impressive scale.

The government, therefore, both fought the communists, and learned from them. Or rather, they fought them first,

and then they learned from them. Their various

encounters with the communists

affected the future of India as a whole in many ways.

This section will highlight two.

First, some of the oppressive measures used against

the movement came to be

incorporated into the new nation’s constitution.

Secondly, the development work of

the communists encouraged the government to adopt its

own programme of uplift for

the peasantry.

While the main justification the Government of India used

as they entered Hyderabad

was to end the ‘communal’ violence, they soon found

that the problems in the state

were intimately related to the communist uprising

which was flourishing in the

Telangana region of the state, for the violent

struggle against the Nizam was centred

in Telangana and led by communists.

rest of India. Rural areas also lacked facilities for

medical care and education. These